This is the first in a new multi-part series by Sanders and Schneier going into depth on real-world examples of democratic technologies from their book, Rewiring Democracy: How AI Will Transform Our Politics, Government, and Citizenship

When we first heard the name Takahiro Anno a year ago, the then 33-year-old had just mounted a longshot bid for governor of Tokyo. He lacked the backing of any established political party, but won more than 150,000 votes.

That’s not an easy feat for a political newcomer with essentially no resources—no funding for advertising, no campaign apparatus, no political organization. Anno adopted a strategy that differentiated him among the candidates.

He practiced broad listening at an unprecedented scale for an independent candidate, engaging with voters and seeking to learn deeply from their lived experiences and policy preferences. Anno, a software engineer by trade, invented new political technologies and leveraged AI to amplify his individual capacity to listen. He used an AI avatar trained on his political manifesto to respond to 8,600 questions from voters over a seventeen-day continuous livestream.

We mentioned Anno in our book on AI and democracy. His story was included among dozens of vignettes about how AI is being used around the world among the many candidates, politicians, advocates, judges, corporations, and others vying for power in democratic systems.

Like others from the US, Europe, South America, and elsewhere, Anno innovated new ways to cross the gulf between politicians and voters. Even a year ago, examples like Anno’s could easily be dismissed as failed experiments and publicity stunts: he came in fifth in the gubernatorial race out of a field of 56. At best, the examples were suggestive of what AI may someday be used to accomplish.

For AI in general, and for Anno in particular, a lot has changed in a year. In July, Anno ran again and won. He is now an elected member of the House of Councillors, the upper Chamber of the Diet, Japan’s national legislature. As part of Anno’s candidacy, he and collaborators from his gubernatorial campaign the previous year founded a new Japanese political party, which received more than 1.5 million votes nationally. The party name, Team Mirai, can be translated as “the Future Party,” with a non-coincidental “AI” suffix. Eager to demonstrate that his promise of “Digital Democracy” is more than a stunt, Anno and Team Mirai have accelerated the development of technologies to realize that vision.

Anno’s Democratic Innovations

Between his two candidacies, Anno founded the Digital Democracy 2030 project, a philanthropically-funded effort to create a politically neutral, open source “operating system” for democracy usable in Japan and around the world.

Speaking to us in November on video, along with his colleagues Shutaro Aoyama and Aoi Furukawa, Anno clearly described the purpose of technology in the Digital Democracy 2030 vision. While acknowledging that the tools and practices are still not mature, Anno said their agenda is to overcome three specific challenges of politics and governance: how to involve many voices in policymaking, how to elicit deep and meaningful input from each voice, and how to extract meaning and actionable insight from those in-depth perspectives.

Collecting Perspectives

The Mirai AI Interview app illustrates how Anno has leveraged existing social platforms to take advantage of their reach, while trying to overcome their limitations of shallow conversation. Team Mirai configures the AI interviewer to engage users on a particular topic, and then broadcasts a link and invitation to engage on platforms like Twitter. As of December 7, the Interview app’s own dashboard reported more than 8,200 interviews taking place on the platform across about fifteen consultation topics, totalling about five thousand hours of interview time.

Nearly a third of that interview time was devoted to consulting respondents on a bill proposing to reduce the size of the Diet. Each individual user session is anonymously published and reviewable. Scanning through these, one sees immediately that they represent something different than a traditional political survey or poll.

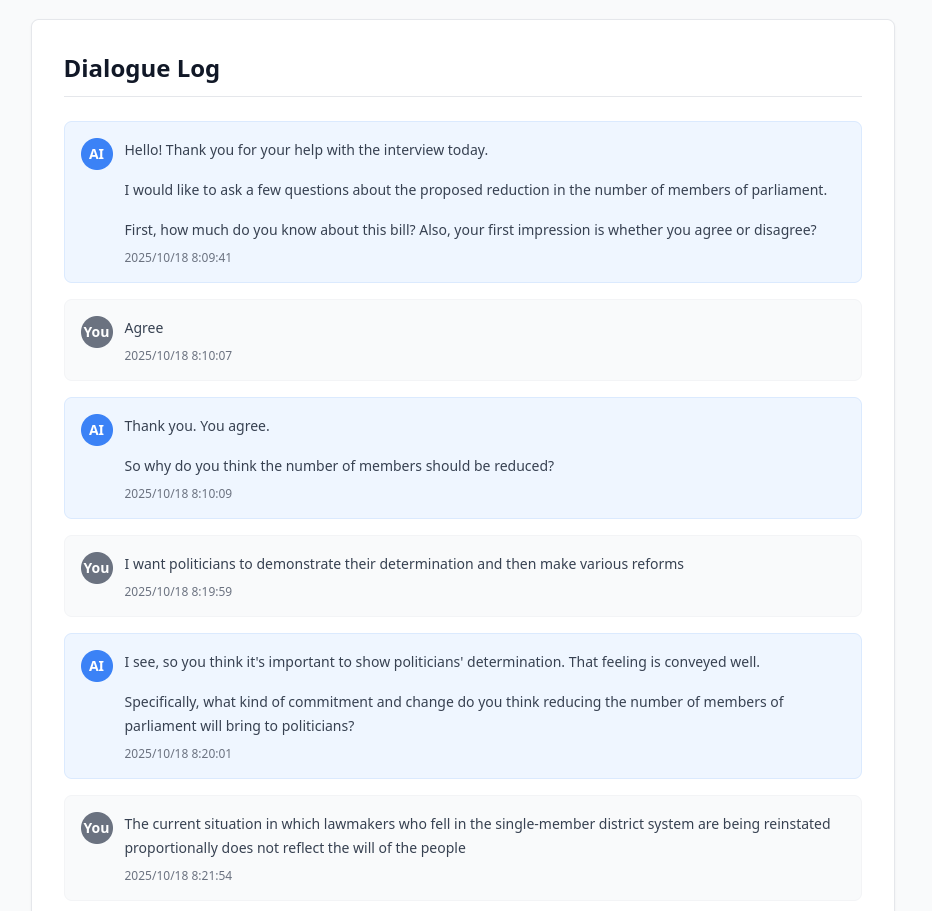

One interview on October 18 covered a range of topics across a forty-minute session, which elicited about two dozen responses from the human interviewee. The AI interviewer posed broad questions of relevance to the consultation, like ”Do you agree that the Diet should be shrunk?” and then prompted the human respondent to think through and explain their reasoning: ”Why do you feel that a reduction would better align the parliament to the popular will?” The AI interviewer then probed how the respondent’s position translates to specific scenarios: What if the change were to the number of proportional representation seats rather than the total size of the Diet?

Ultimately, the respondent pushed back on the AI’s attempts to go into the structural details of the system, and drove home a different message instead—the Diet must show that it is capable of reform, and implementing a size reduction would be an easily-understandable way to show the public they’re up to the job.

The initial exchange of a longer session between Mirai AI Interview and a respondent to a consultation about changing the size of the Diet, from October 18 (machine translated).

An AI-generated summary of the Diet size reform consultation condenses more than 36,000 messages exchanged between people and the AI Interview app into thirteen key findings backed by dozens of citations to individual perspectives shared on the app. While most conversations are short, and not all rise to the level of sincere engagement and substance, sessions like the one described here illustrate the point that an AI interlocutor can enable deep listening among constituents at scale, and that some people are willing to engage in this mode.

The Mirai AI Interview tool is an evolution of a practice Anno started during his 2024 gubernatorial campaign. He posted his political manifesto to a GitHub repository—the system developers use to contribute changes to software—and invited the public to suggest changes. Ultimately, the team developed the Idobata software (roughly translated: water cooler chat) to provide a friendlier interface for proposing policy changes. Instead of making a change on GitHub to suggest a tweak to the manifesto, you can express yourself to a chatbot, and it will file the change request for you.

Mobilizing action

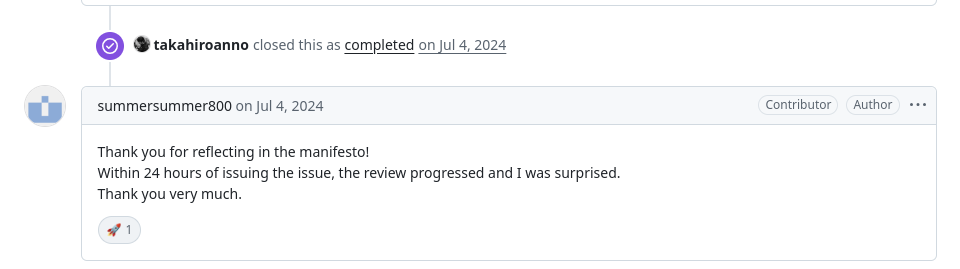

We asked Anno for an example of a meaningful policy change he adopted as a result of this system. He gave the example of a suggestion by GitHub user sumersummer800 from July 2024, to expand his public health platform to provide public funding for the RSV vaccine for pregnant women. After only one day, the user could see their specific changes accepted and adopted into Anno’s platform. (Nineteen months later, this became actual policy in Japan.) The direct and visible impact of the user’s engagement is part of the process: The role of technology here, in part, is to provide positive feedback in return for political action.

A user’s proposed change to Takahiro Anno’s 2024 policy platform for public health is accepted (machine translated).

Only eighty-seven change suggestions like this were accepted in Anno’s 2024 platform, some of which were more technical updates than substantive policy changes. After implementing the Idobata chatbot, the scale of engagement grew dramatically. Team Mirai’s “version 1.0” policy manifesto received about 9,700 suggestions—98% of which were generated by the Idobata bot—and accepted 348 of them (190 of which came from the bot).

Despite the scale of constituent engagement (and AI assistance) involved in this process, the policy manifesto itself remains unmistakably and fully accountably Anno’s. The Idobata bot translates conversations with people into proposed amendments to Mirai’s platform, but Anno decides which proposals to accept.

Anno told us that he realizes these broad listening tools can be systematically biased. Perhaps a self-selecting subset of the population uses the tools. Perhaps the AI tools reflect an incomplete or shaded representation of the human input they receive. Anno’s current solution is not to use the tools like vote counters—he knows he won’t receive a scientifically representative sample of users—but as mechanisms for surfacing a breadth of perspectives, making him more aware of his constituents’ diverse views.

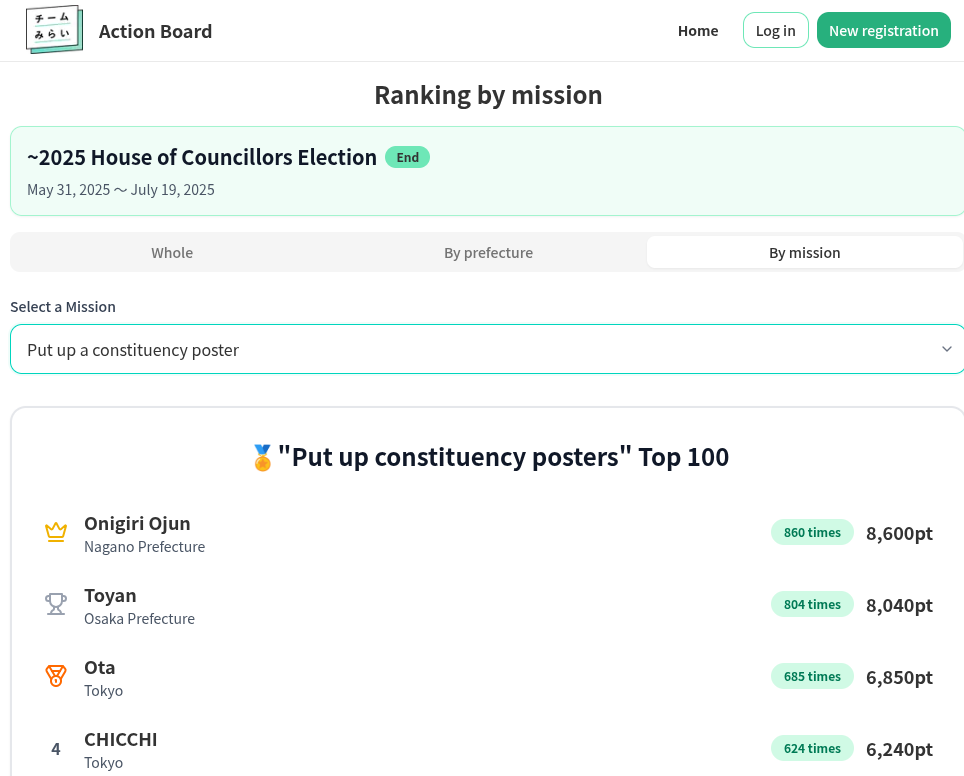

Team Mirai’s tools encourage their supporters to take action beyond participating in their own policy development process. The Action Board is a gamified volunteer activation platform. Users who register are awarded points and recognized on a leader board when they take political actions directed by Team Mirai, such as following their social accounts or reposting their content, putting up posters or distributing flyers, volunteering at events, or making a policy suggestion. As of late November, more than 240,000 actions by more than 19,000 users were registered. At least one other Japanese political party, the Democratic Party for the People, has adopted and launched their own Action Board.

A volunteer leaderboard on the Mirai Action Board from the 2025 Diet election campaign (machine translated).

Guiding the party

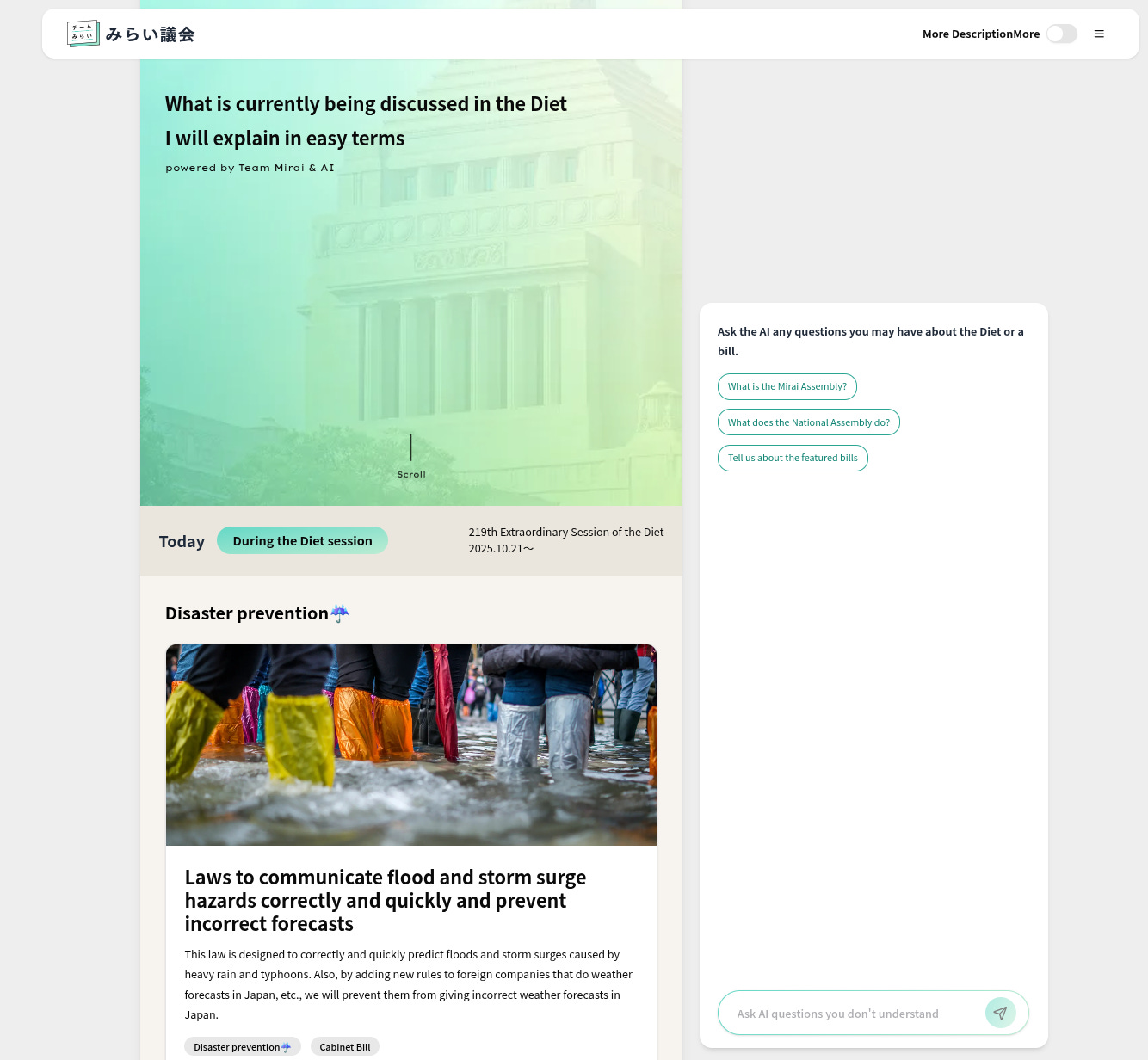

One of Team Mirai’s more recent innovations is the Mirai Gikai, translating to “Assembly” or “Parliament” app. The app looks like a live, AI-generated newsfeed of what’s happening in the Diet. The app includes a page for each bill with information about its status in the legislature, a summary of its effects, and links to news reporting about related issues. When the party, Team Mirai, has a stance on the issue, it is posted to the page. An AI chatbot on the side allows users to ask specific questions. Released this October, Team Mirai reported that the open source tool received 440,000 views in just its first two days.

The Mirai Assembly (Gikai) app surfaces information about bills under active discussion in the Diet, and provides an AI chatbot to explain and contextualize those proposals (machine translated).

Of all the things Team Mirai has built, the team itself may be the most unique in Japanese politics. Now that it has representation in the Diet, Team Mirai receives a share of the public funding for political parties allocated under the 1994 Political Party Subsidies Act. They are using the funds, in part, to hire engineers like Jun Ito, lead developer of their recently released financial transparency platform, Marumie (roughly translated: transparency). Anno has estimated that the party’s annual share of public funding will be about 100–200 million yen (about $600,000–$1,200,000 US dollars).

Earlier this year, Anno described Team Mirai’s investment in technology as a shared project. In addition to open-sourcing the code behind many of their applications, Anno wrote that Team Mirai would be a “ユーティリティ政党” (utility party) for Japanese government and politics, providing technical collaboration to help other institutions adopt the tools they’ve built. In Anno’s words (translated by machine): “I would like to open up discussions that have not been held before, that have been decided solely within [the Diet], while also realizing a new, open policy-making process.”

A Party of the Future

As one of 248 members of the House of Councilors, Anno now has a real share of political influence in Japanese policymaking, and an ambition to go further. In our interview, Anno positioned his party along both traditional and novel axes of Japanese politics.

WIth respect to the traditional left-right axis, he claims the center between the ruling Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) and its hoshu (approximately: conservative) principles and the now-largest opposition party, the Constitutional Democratic Party of Japan, and their kakushin (approximately: progressive) principles. But Anno also described a second axis, spanning from the status quo politics of those larger, traditionalist parties to an opposite, previously unpopulated part of the spectrum he describes as “the future.” On that axis, Anno says, his party is a vanguard: They are staking a claim on territory that represents the future of Japanese politics.

Anno’s politics reflect an emerging reality: the traditional left-right divide is no longer the dominant political frame for younger Japanese voters. As political scientist Endo Masahisa has written, young voters now “view the focus of partisan conflict as the struggle between reform and the political status quo.” Japan’s economy is dominated by concerns about population decline and the social needs of the largest, aging generations, but its politics is only starting to reorient to those challenges.

By Anno’s description, Team Mirai is addressing the unmet needs of younger and urban voters seeking reform of both the political system and the economy. The headline of their political manifesto translates to “Creating a Japan where no one is left behind through technology.” In an independent evaluation by Waseda University’s Democracy Creation Research Institute, Team Mirai’s 2025 manifesto was top rated among all Japanese political parties on criteria that included clarity of vision, consistency, specificity, and civic participation.

AI as a tool, practical and political

The secret to Team Mirai’s remarkable productivity in prototyping and releasing new civic technology platforms is that their small team does not build everything themselves: They have artificial assistance. Anno, who—from his elected office—still serves as the lead engineer for some of their technology products like the Mirai AI Interview, describes the team as heavy users of the agnostic AI coding assistant Claude Code.

Team Mirai’s strategy incorporates AI not only for tool building but also for their political platform. Consider this (machine) translated excerpt from their manifesto:

“AI increases uncertainty… This is also an opportunity for Japan if we change our perspective. The era of new technologies is one in which winners and losers tend to switch places. While the previous two major technological changes—the internet and the birth of smartphones—have left us behind, this time there is still an opportunity. In the race to build AI, Japan is far behind the US and China, but the race to master AI has only just begun.”

Team Mirai’s vision will have dissenters: on the centrality of economic growth to Japan’s future, the commercial potential for AI to deliver that growth, and the geopolitical positioning of Japan among an international industrial race associated with technology. But Team Mirai is undeniably positioning itself to capitalize on the salience of these issues and the failure of traditional parties to attend to them.

A Mirai (Future) Beyond Japan

Anno has credited former Taiwanese Digital Minister Audrey Tang and her work building platforms for broad listening in Taiwan as inspiration for Team Mirai’s vision of digital democracy. Tang’s works include vTaiwan, the decentralized consultation process she helped establish outside of government, as well as Join, its institutionalized successor she built within government. But Anno intends to do things differently, too.

In a discussion this February, Anno reported his team’s conclusions following a tour of Taiwan and meetings with civic technologists there. The use of Join has contracted in Taiwan, he says, and lost its “star” steward when Tang departed government, as well as its engineering support. Anno argues that any digital democracy products Team Mirai produces must be able to function sustainably without a charismatic leader, and in a fully automated way that can outlast any potentially short-lived investment in human facilitation. To avoid participation fatigue, constituent inputs to digital democracy platforms must be visibly followed by political actions and signals of implementation.

Team Mirai recently put out a call recruiting more candidates to join Anno in running for office under the party’s banner. Anno told us that they are interviewing those potential candidates now, with a focus on representation of younger candidates from urban areas.

Due in no small part to leaders like Tang and Anno in Taiwan and Japan, East Asia has emerged as a hotbed of digital democracy innovation. How translatable these efforts are to other countries, continents, and cultures remains to be seen. In addition to dramatic differences among political systems, recent research from Pew has exposed marked differences in levels of comfort with AI around the world; Americans were about two times more likely than Japanese to say they are more concerned than excited about AI’s increasing role in daily life. (Young people in Japan reported the greatest level of comfort of any age demographic in any country surveyed.)

The technologies of artificial intelligence are broadly power-enhancing. In the hands of people who want to dismantle democracy, AI will help do that. In the hands of people who want to make democracy better–more agile, more responsive, more democratic–AI can help, too. Anno and Team Mirai are vanguards of this latter movement. We are watching whether they will inspire a younger generation world-wide to embrace digital technology that makes democracy more participatory, responsive, and successful.